Ansel Adams Photography

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand.” - Ansel Adams

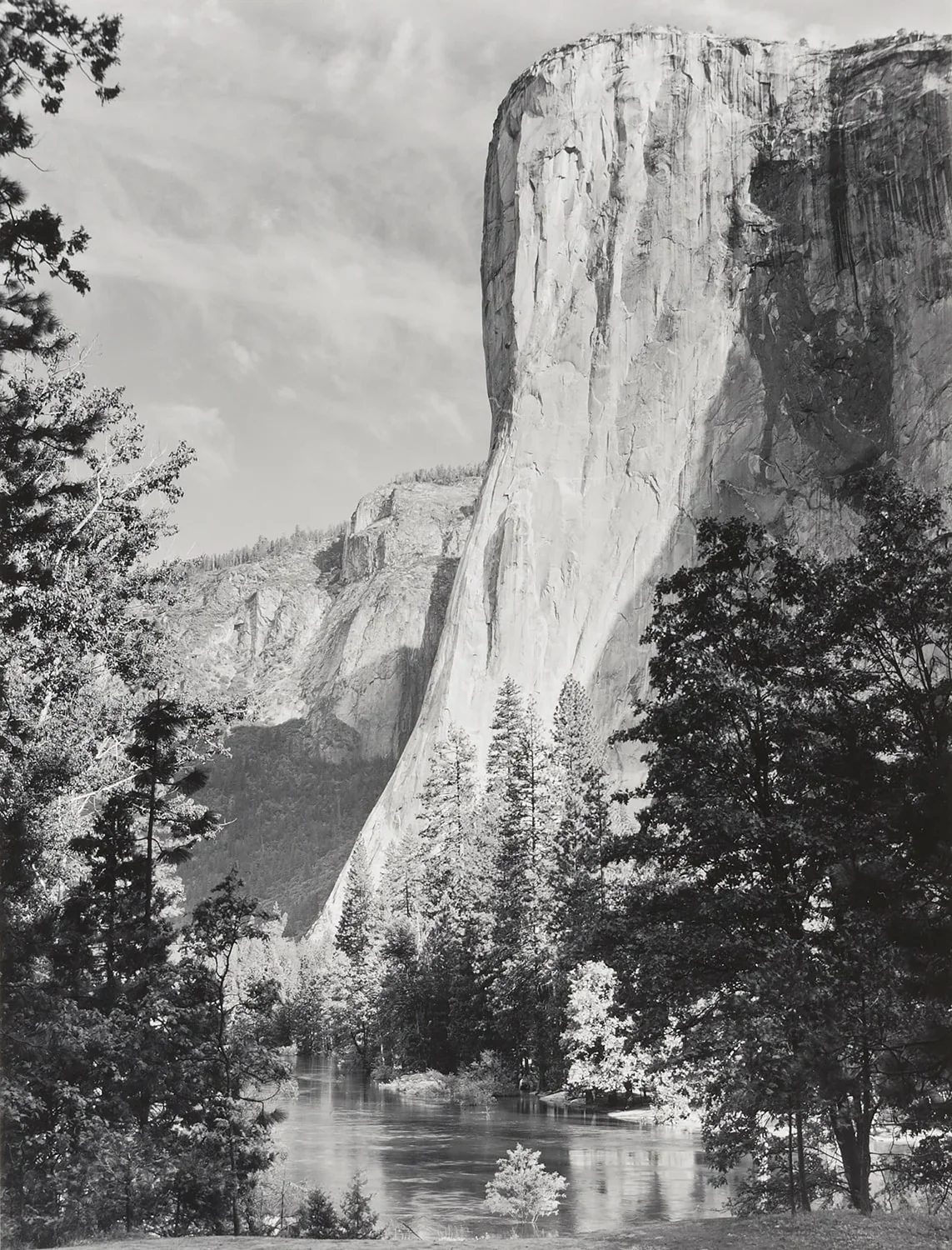

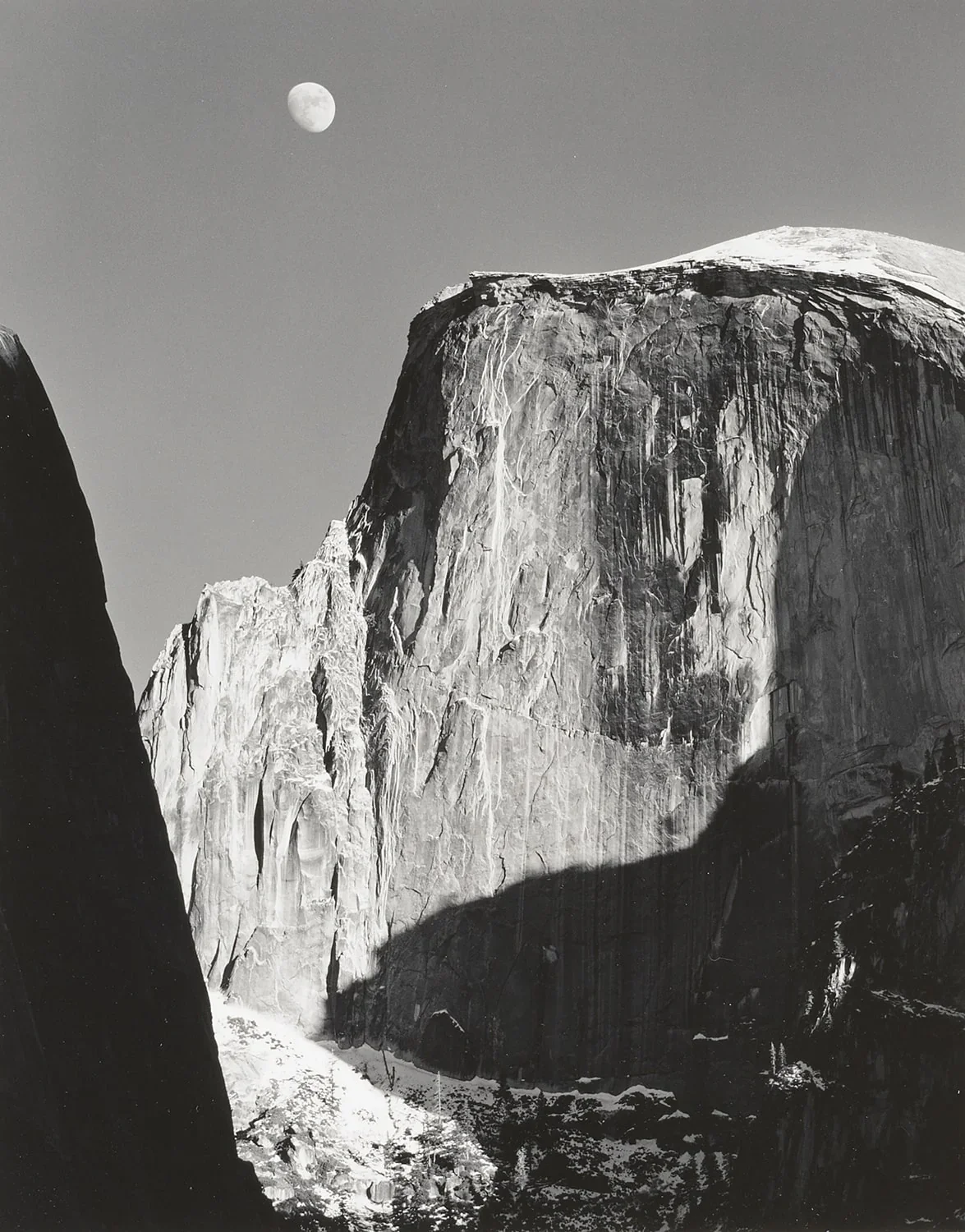

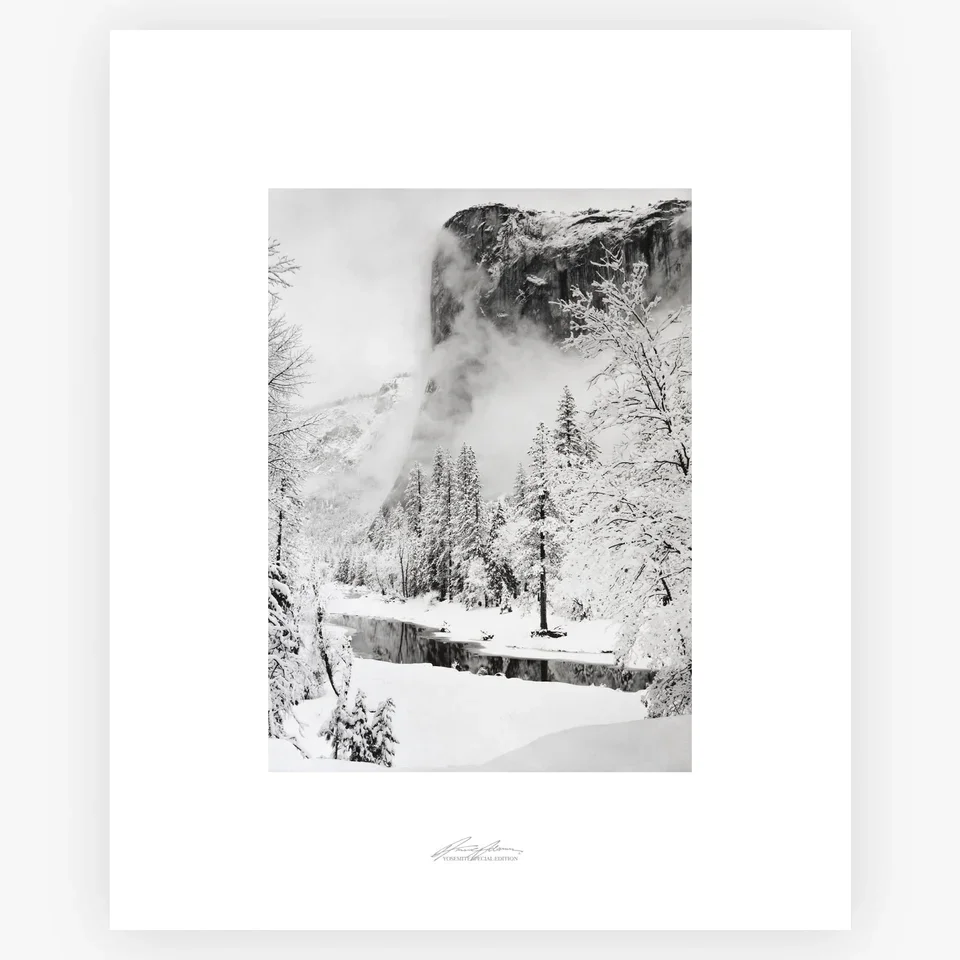

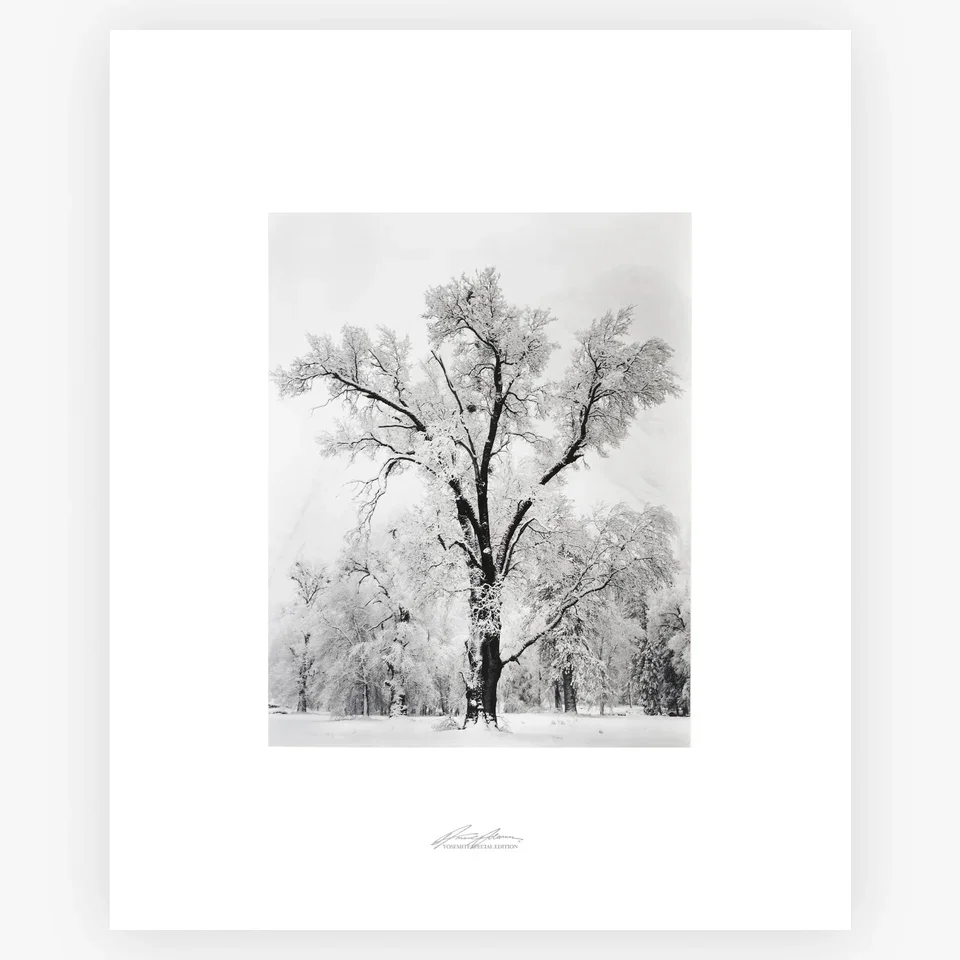

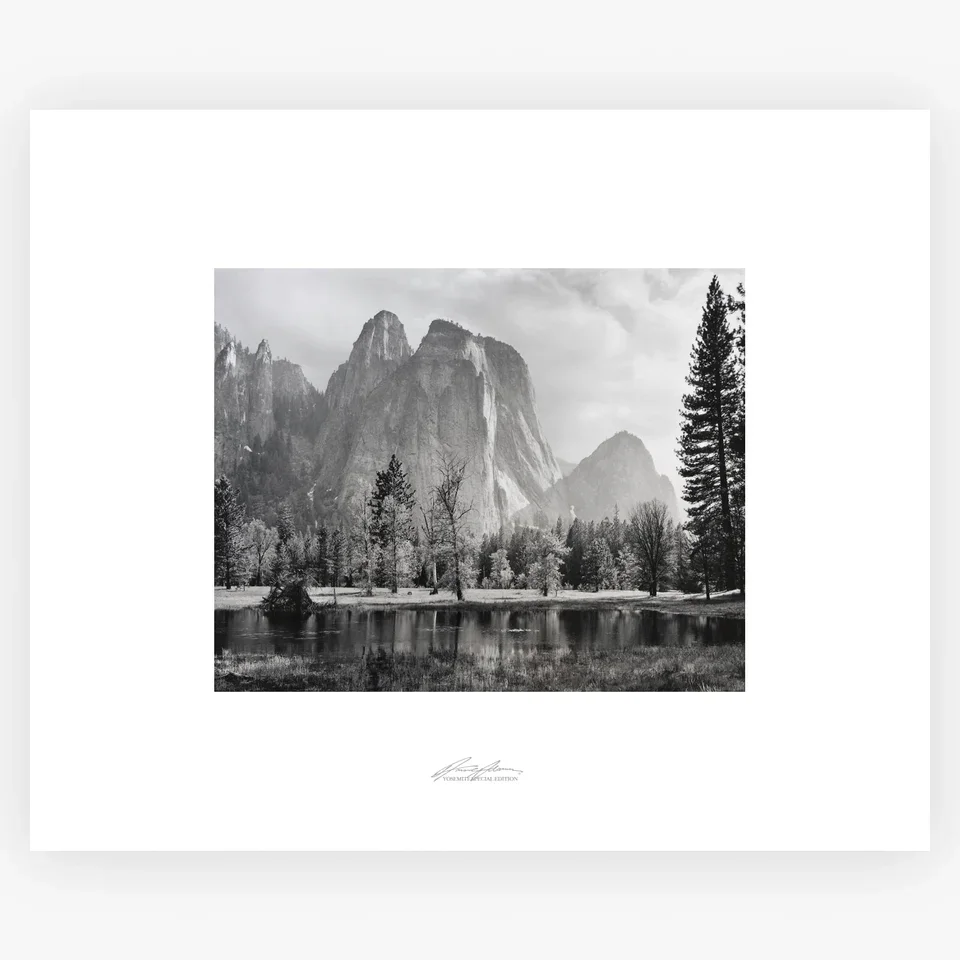

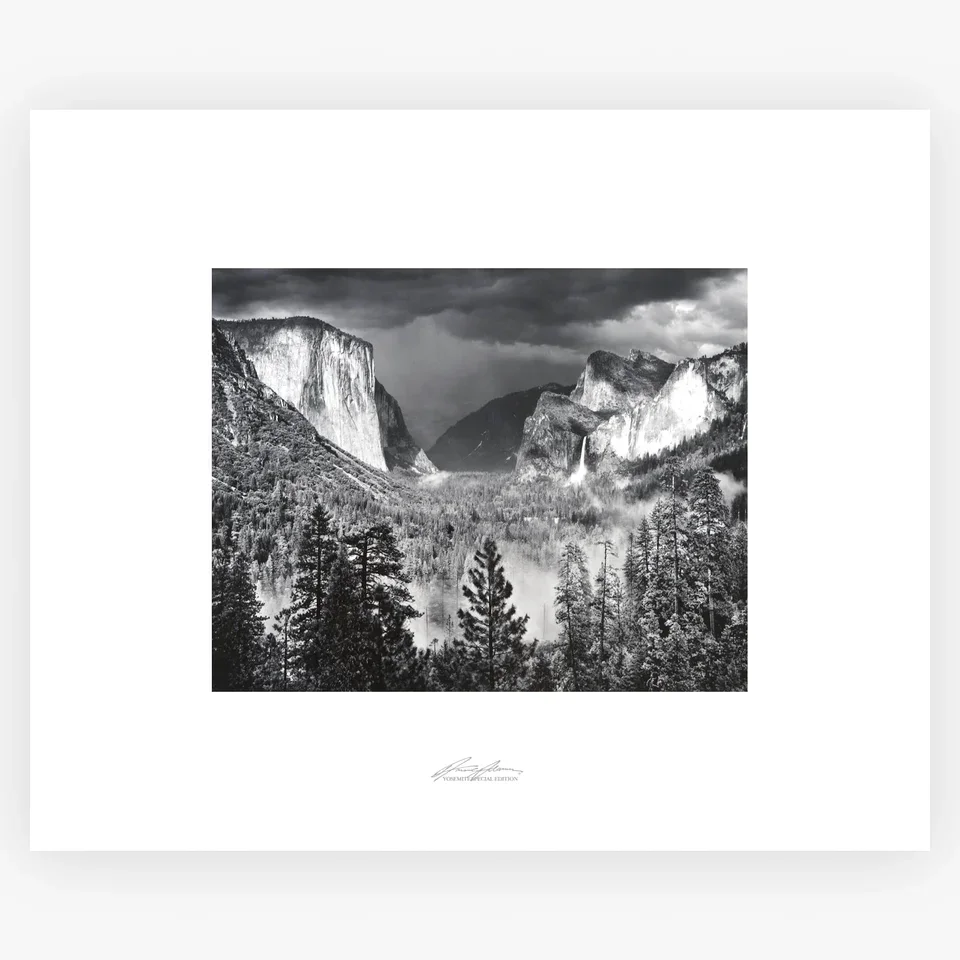

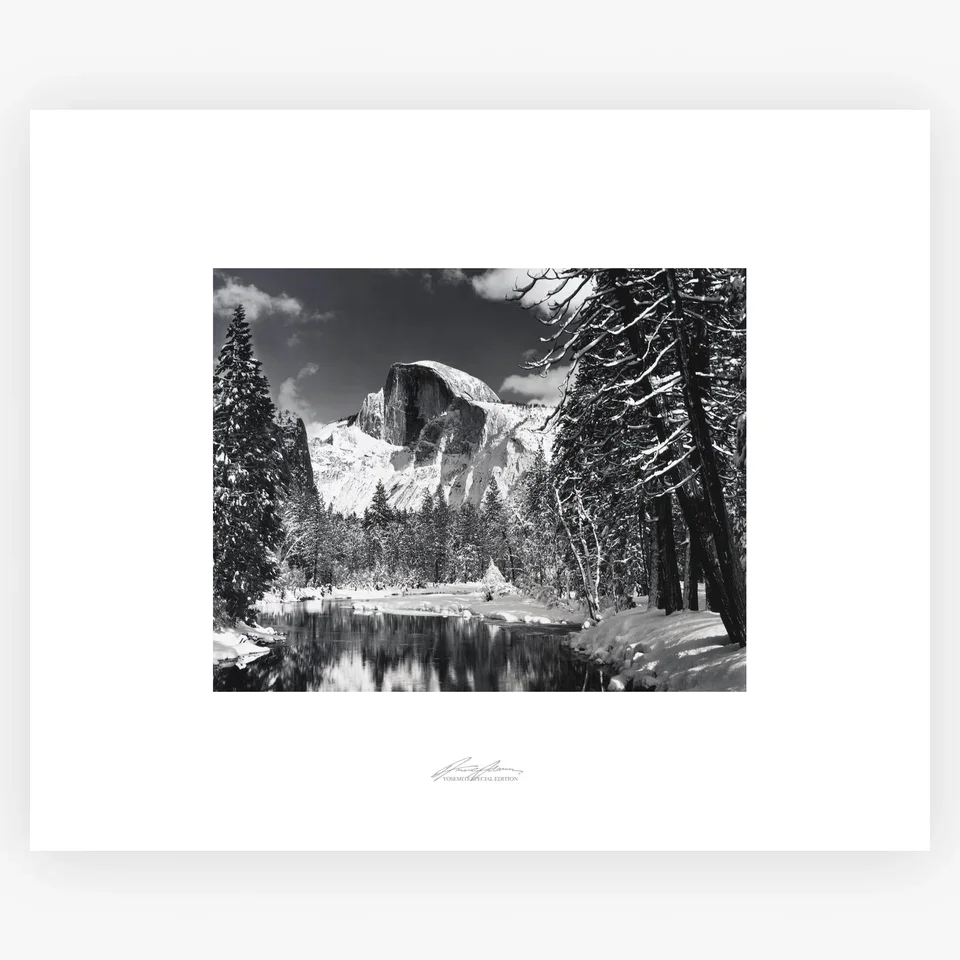

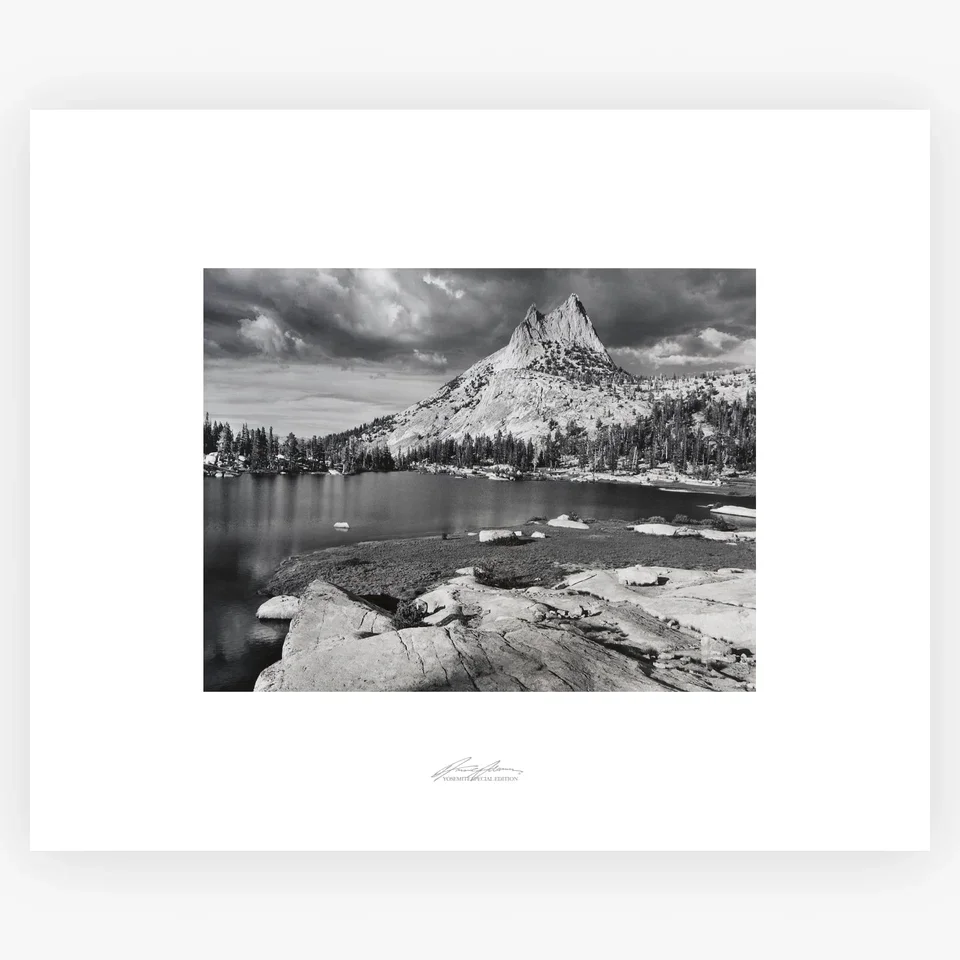

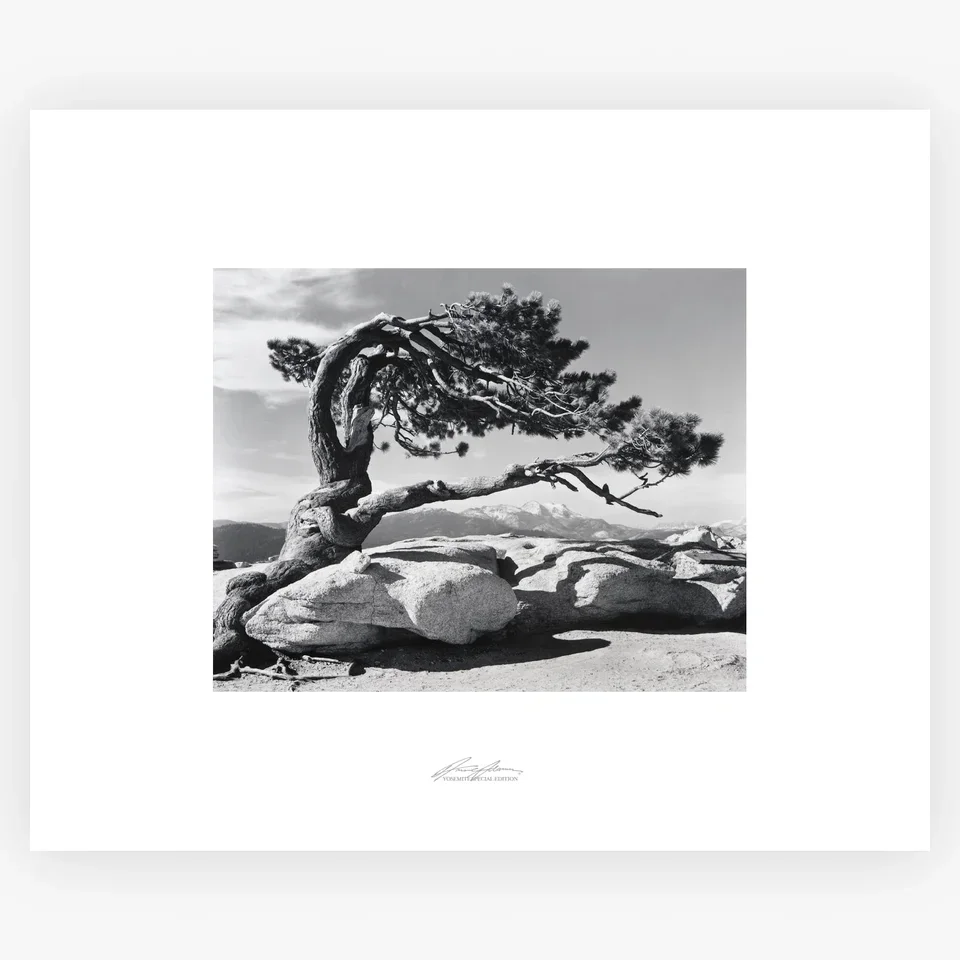

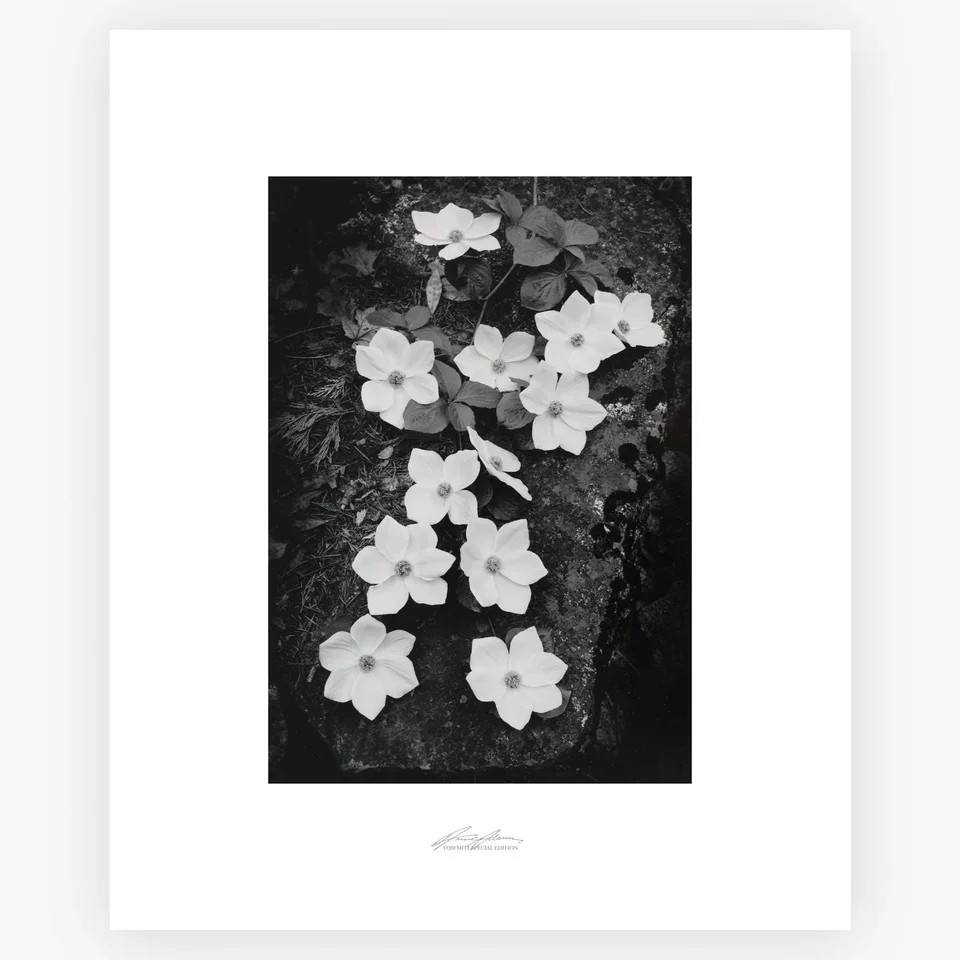

Ansel Adams remains one of the most celebrated photographers in history, his name inseparably linked with the vast wilderness of the American West. His sharply detailed black-and-white images of Yosemite Valley, the Sierra Nevada, and the desert Southwest not only elevated photography to the level of fine art but also helped inspire a national movement toward environmental preservation. To understand Adams is to see how one man’s lens could shape both artistic traditions and public consciousness.

The Ansel Adams Gallery

The Ansel Adams Gallery welcomes visitors seven days a week, from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., closing only on Thanksgiving and Christmas Day. Set in the heart of Yosemite Valley—between the Visitor Center and the Post Office—it offers sweeping views of Yosemite Falls, Half Dome, and Glacier Point. The staff, a spirited mix of climbers, photographers, hikers, dog lovers, and devoted admirers of the park, embody the same passion for wilderness that defined Adams himself. As an authorized concessioner of the National Park Service, the gallery continues to honor his legacy while inviting travelers to experience Yosemite through both art and place.

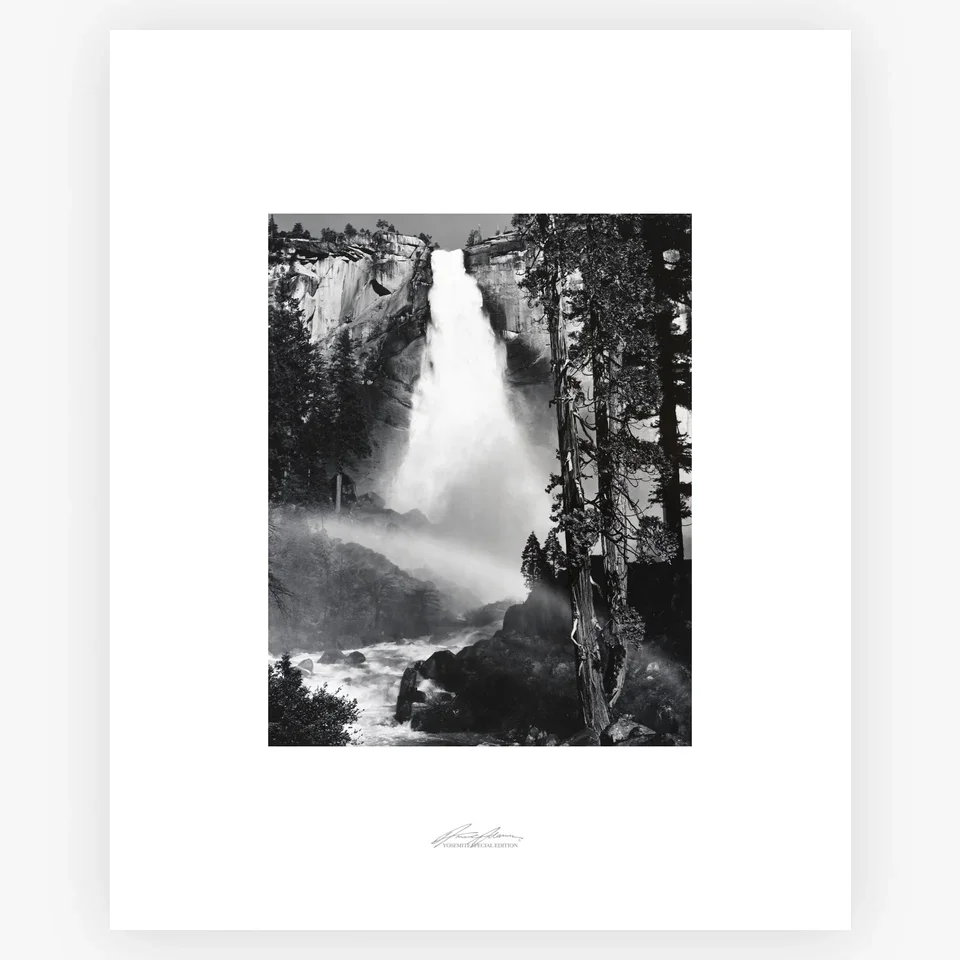

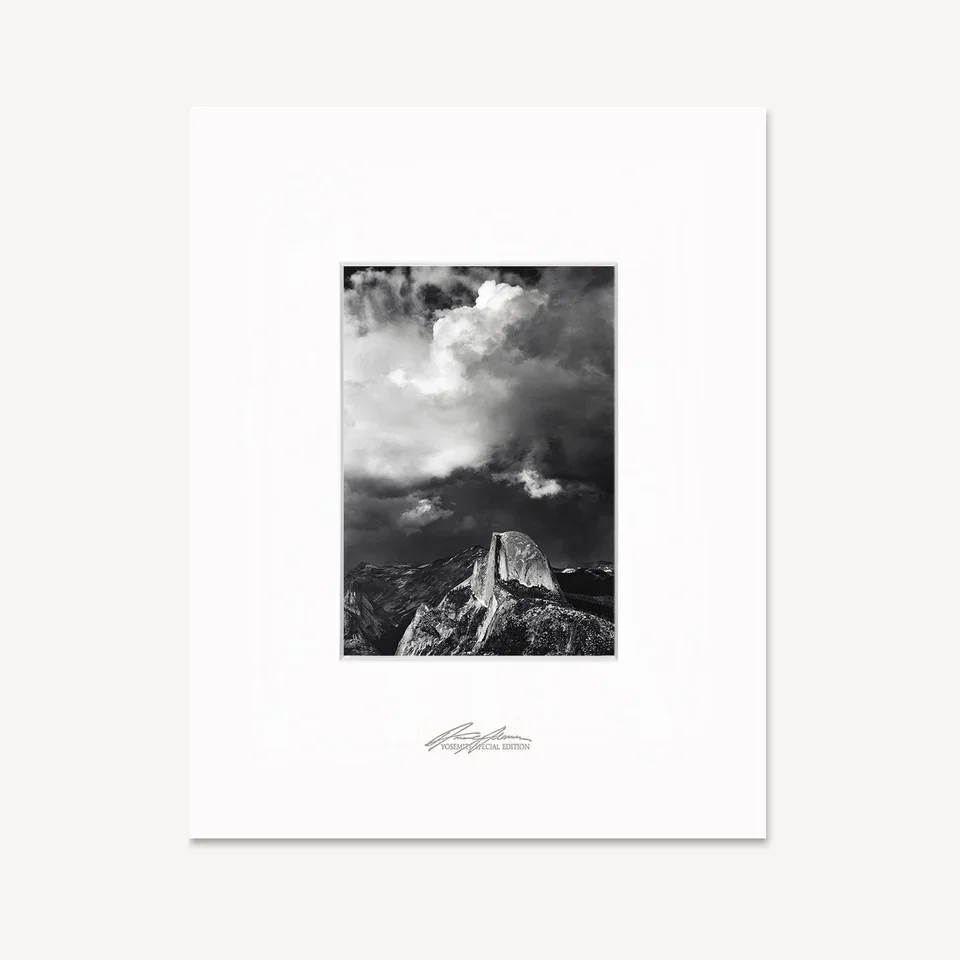

Click Photo to Enlarge

Early Life and First Encounters with Yosemite

Adams was born on February 20, 1902, in San Francisco, just two years before the great earthquake that would devastate much of the city. A restless child, he struggled in school due to dyslexia and a temperament ill-suited for rigid classrooms. His parents, particularly his father Charles, encouraged him to explore interests beyond academics, nurturing a fascination with the outdoors.

“Ric Burns Created an Exceptional Documentary.” - Coast & Cottage