Becoming Mark Twain

The River, the Pen, and the Making of an American Legend

A Boy Named Samuel

Before there was Mark Twain, there was Samuel Langhorne Clemens, a freckle-faced boy born in the tiny Missouri hamlet of Florida in 1835. His childhood unfolded in nearby Hannibal, a bustling river town perched on the banks of the mighty Mississippi. Hannibal was equal parts playground and schoolroom, with steamboats churning upriver, gamblers and traders milling about the docks, and the looming specter of the Civil War stirring unrest.

Sam was a curious, mischievous soul—drawn to storytelling from the start. The rhythms of the river, the dialects of neighbors and drifters, the dark corners of caves and the wide open promise of the Missouri landscape—all of it lodged in his imagination, waiting for the day it would pour back out as tales of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

The Books of Mark Twain

The Steamboat Years

In his youth, Clemens apprenticed as a typesetter and wrote humorous sketches for local papers. But the river called him back, and he pursued his dream of becoming a steamboat pilot—a position of great skill and prestige in those days. It was on the Mississippi that he encountered the phrase “mark twain,” a riverboatman’s call meaning safe water depth. Years later, he would adopt it as his pen name, a salute to the river that had shaped him.

Steamboating was exhilarating but perilous. When the Civil War broke out, river traffic slowed to a trickle, and Sam’s piloting career abruptly ended. He briefly flirted with Confederate military service before heading west to the Nevada Territory, where his destiny as a writer would truly take shape.

Becoming a Writer

The Nevada frontier was a rough-and-tumble place, full of prospectors, dreamers, and scoundrels. Clemens worked as a journalist for the Territorial Enterprise, honing his sharp wit and flair for satire. It was here, in 1863, that he first signed an article as “Mark Twain.”

His breakthrough came in 1865 with the publication of The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, a humorous story that swept through newspapers nationwide. The piece marked Twain as a fresh voice—irreverent, distinctly American, and unafraid to lampoon the powerful.

The Literary Riverboat

Twain’s works flowed like tributaries branching off the Mississippi. The Innocents Abroad chronicled his travels through Europe and the Holy Land with a blend of humor and sharp observation, making him one of the most widely read authors of his era. But it was The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) that cemented his legacy.

Huck Finn, in particular, remains a cornerstone of American literature, capturing the complexities of race, freedom, and morality in a young nation still grappling with its conscience. Twain’s gift lay in his ear for dialogue and his ability to elevate the voices of everyday people—gamblers, slaves, scamps, and dreamers—into unforgettable characters.

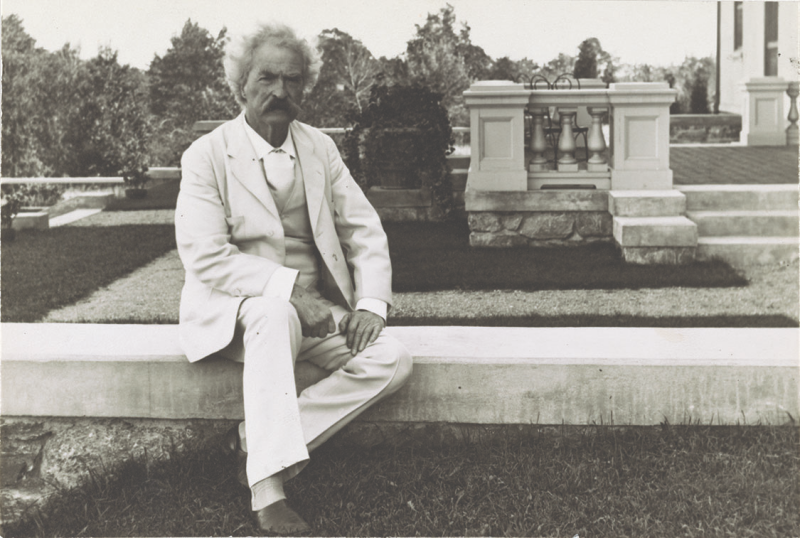

Beyond fiction, Twain became a sought-after lecturer, traveling the world and delivering talks that blended comedy, storytelling, and biting social critique. His stage presence was magnetic; audiences hung on every quip and yarn.

Article by Harry Katz